Welcome to Thursday Things! If you enjoy this edition, please click the heart icon in the header or at the end of the post to let me know. You can post a comment by clicking the dialog bubble.

“Not me. I’m a nice tree!” Photo by Todd Quackenbush on Unsplash

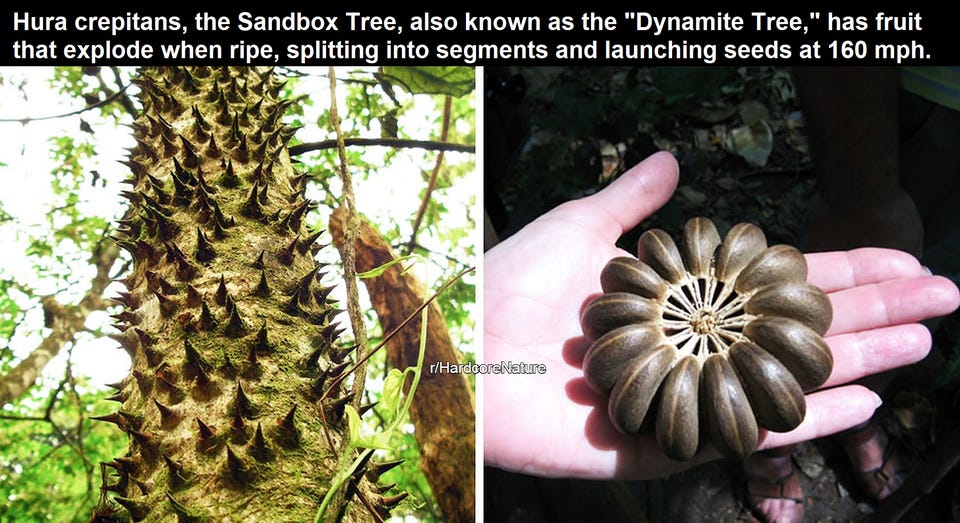

Tree of death. How is this tree even a real thing? I learned about the homicidal sandbox tree, native to South America and some parts of North America, only this week. What is a sandbox tree and why should it be called the murder tree instead? Read on!

What Is A Sandbox Tree: Information About Sandbox Tree Exploding Seeds

Considered one of the most dangerous plants in the world, the sandbox tree isn’t suitable for home landscapes, or any landscape actually.

Well, that sounds promising.

A member of the spurge family, the sandbox tree (Hura crepitans) grows 90 to 130 feet (28-40 m.) tall in its native environment. You can easily recognize the tree by its gray bark covered with cone-shaped spikes.

Spikes. Great. So don’t touch it and you’re safe, right?

Ha.

Sandbox tree fruit looks like little pumpkins, but once they dry into seed capsules, they become ticking time bombs. When fully mature, they explode with a loud bang and fling their hard, flattened seeds at speeds of up to 150 miles (241 km.) per hour and distances of over 60 feet (18 m.). The shrapnel can seriously injure any person or animal in its path.

Yes. A tree that produces and throws its own shrapnel grenades.

At least they’re organic.

Okay, so I’ll stay at least 60 feet away from the tree at all times. Then I’m safe, right?

As bad as this is, the exploding seed pods are only one of the ways that a sandbox tree can inflict harm.

This gets better and better.

The fruit of the sandbox tree is poisonous, causing vomiting, diarrhea, and cramps if ingested. The tree sap is said to cause an angry red rash, and it can blind you if it gets in your eyes. It has been used to make poison darts.

Honestly, I wasn’t planning to eat any of the exploding death fruit anyway. But good to know it’s also poisonous. Because of course it is.

The sandbox tree does have some redeeming qualities. Oil from the seeds, various extracts from the tree, as well as the leaves have medicinal uses. Even so, the article concludes:

You should never plant a sandbox tree. It is too dangerous to have around people or animals, and when planted in isolated areas it is likely to spread.

I just know someone is planting these things in Florida right now.

Just be glad these things can’t walk. Source: Reddit

The good old days were pretty crooked. Professional Running: the Nineteenth Century’s Dirtiest Sport

In the nineteenth century, professional running had a “reputation for deception,” explains librarian Lisa R. Lindell. It “was subject to trickery and race fixing and rewarding of those athletes who worked the system to their advantage.” That era of the sport—with all of its possible shenanigans—is illustrated in the life of James “Cuckoo” Collins.

“Running, walking, and jumping competitions, known collectively as pedestrianism, were among the most popular sporting events,” Lindell explains. But like many sports of the time, pedestrianism was full of gambling. Maximizing those winnings, which would also be enjoyed by the racer, usually meant a little bit of trickery. Runners often collaborated with each other and coaches to fix races, making the outcomes financially determined rather than athletically. American racers “would starve to death if they were honest,” a sprinter once claimed.

Ah, yes, who can forget James “Cuckoo” Collins?

According to his hometown newspaper, his nickname, “Cuckoo,” was a testament to his skills in trickery.

Collins colluded to lose races, ensuring that the only winners would be those who bet against him. He also went the other direction, using a fake name to enter races and “overtook local favorites for the win.”

Alas for Cuckoo Collins, he could not outrun a bullet1 … read the article for the whole story: “Cuckoo Collins: The Crooked Path of a Nineteenth-Century Professional Sprinter”, Lisa R. Lindell, Journal of Sport History, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Fall 2018), pp. 334-351

Time behind bars. I read this interesting piece on how people in prison mark and perceive the passage of time — and what that tells us about time in our own, presumably non-incarcerated, lives. Prison life puts the ‘time work’ we all do into sharp relief

More than most people, prisoners are beset by temporal quandaries. They must traverse a huge expanse of unstructured time, and there are few distractions with which they can occupy themselves. Like most people, they are reluctant to lose track of time, but attention to clocks and calendars will only stretch the perceived length of their sentences. Thus, prisoners engage in what I call ‘time work’ by crafting personal or collective efforts to modify their own temporal experience.

While I haven’t been in prison (so far…) I do know that my perception of time is much altered since I left the “office world” almost a decade ago. Because I don’t have that kind of regular schedule of having to show up at a certain place at a certain time each day, I sometimes am not sure what day it is.2

I suspect people who have gone to “remote work” over the last couple of years may have a modified version of that experience, though if you’ve still got regular online meetings to attend you may still remain more tethered to the space-time continuum than I am most days. Has how you experience time changed as your work, home, or other environment has changed?

Thank you for reading Thursday Things! Again, please click the hearts, leave a comment, and use the share feature to send this issue to a friend who might enjoy it. See you next Thursday!

Or even, probably, a sandbox tree seed.

Except for Thursdays, of course! I always know when it’s Thursday.